Six Ages: Lights Going Out has been Feature Complete for a while. We’re still testing it, and pushing towards Content Complete. One aspect of that is composing the music. The game takes place generations later, and things are very different, so while a few pieces will be the same, most need to be new. (To save time, the various UI-related sound effects will be the same.)

There seems to be no shortage of freelance composers out there, but I sort of accidentally found Neha Patel via Twitter (before Elon Musk began ruining it). We had a discussion about game soundtracks, I checked out her portfolio, and asked her to fill Stan LePard’s shoes. The fact that she knew who he was was a plus (it also speaks well for how Stan tried to help out other composers).

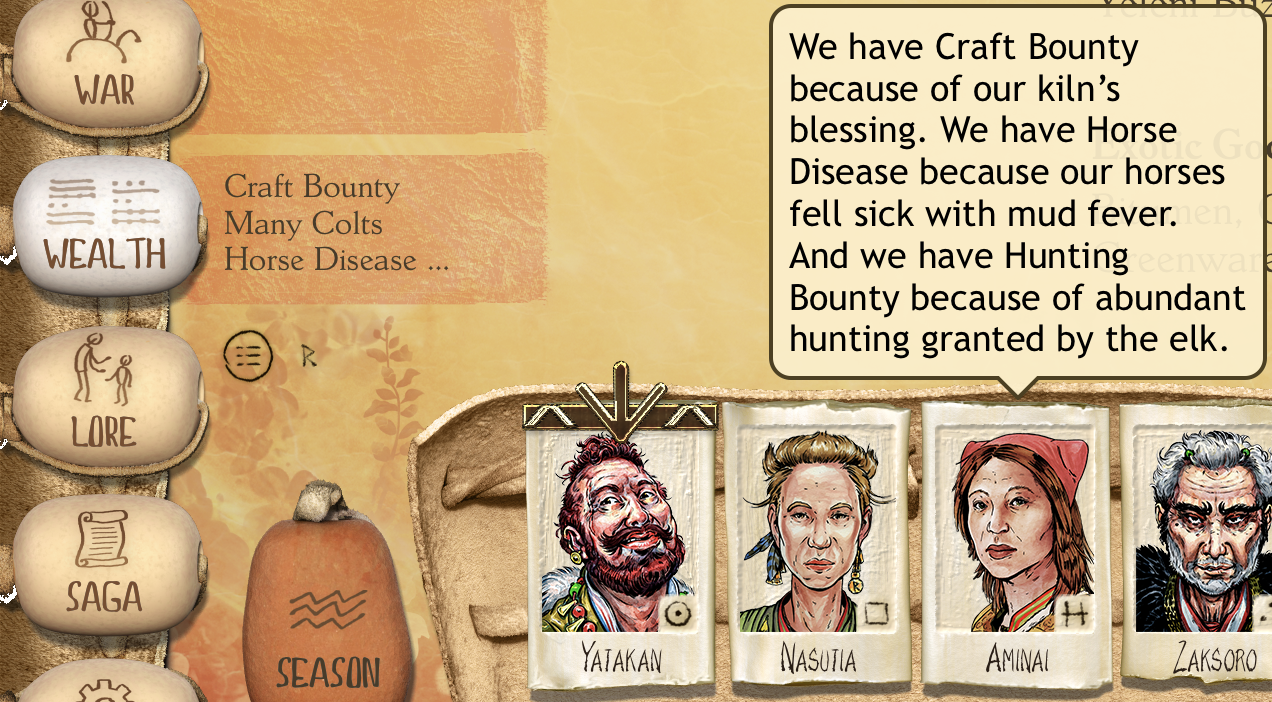

My basic design approach is to look at the events and come up with a couple dozen themes or categories. Many of these ended up the same as Ride Like the Wind — “Strife,” “Request,” “Opportunity” — but some situations are different, and I also decided to add some new categories. So music may be called “InternalPolitics,” “ExternalPolitics,” or “Decay.”

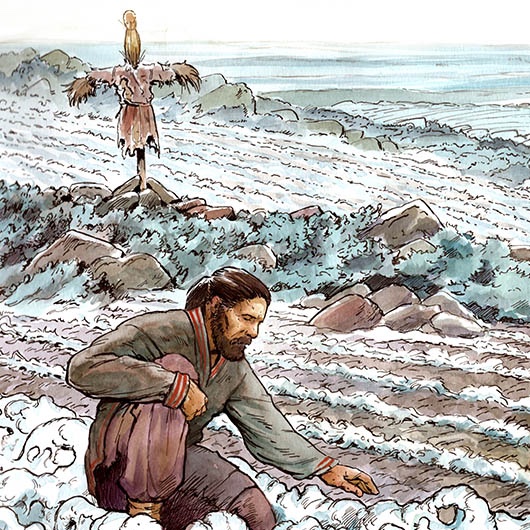

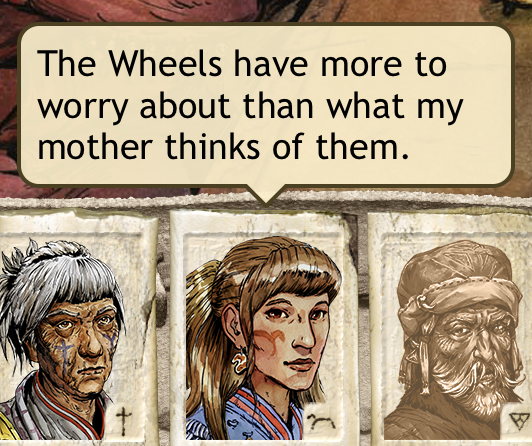

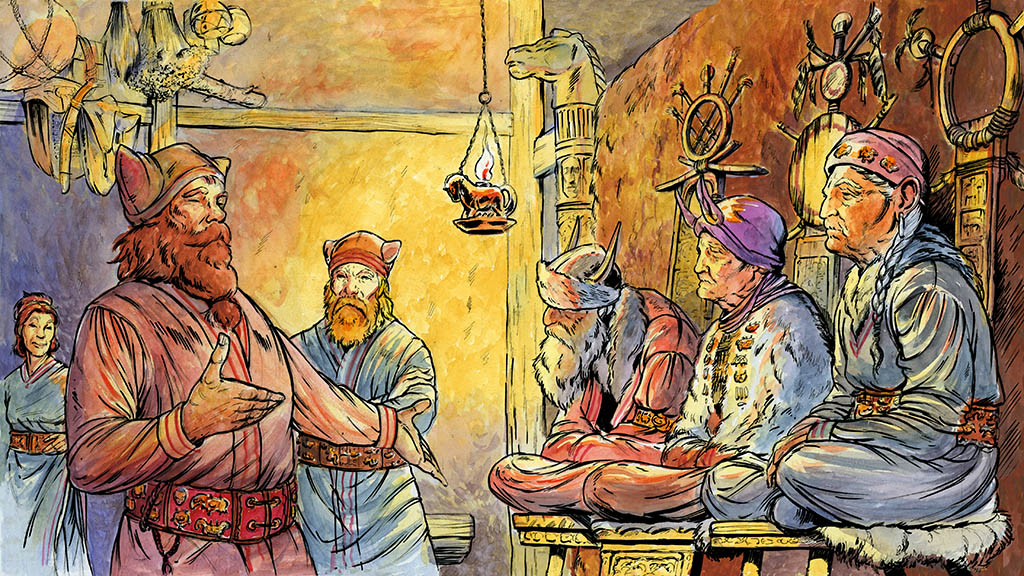

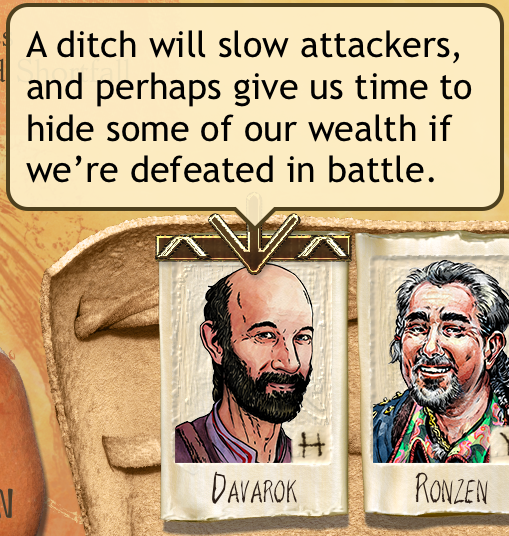

I prepared a list of these, and then for each one, made a short text file describing how the music will be used. I also include 2-4 illustrations to help Neha see the mood we’re after. Here’s Decay:

The world is getting worse

This music is used when the situation involves the overall deterioration of the world. This could be the failure of large political institutions or trade networks, acid rain, crumbling walls, climate change (in this game, it’s cold), greed, imminent starvation, toxic clouds, abandoned temples.

These are all bad situations, but they aren’t overtly supernatural or related to the forces that are explicitly trying to destroy the world.

The purpose of the music is to evoke a feeling, so when Neha sends a draft, I run it by Elise Bowditch, who also reviewed the music for Six Ages: Ride Like the Wind and King of Dragon Pass. I play it without explanation, and get her thoughts. Does it suggest monsters? impending doom? annoying neighbors? Does it feel optimistic or despairing? Elise is good at describing (one piece sounded like a “circus of horrors”). If it doesn’t seem to fit, we may need a completely new approach.

Assuming there’s a plausible match, we can then worry about specifics, like whether crashing cymbals are appropriate or the instruments should be swapped out. Occasionally a piece that really isn’t working can be radically transformed by changing an instrument.

Or sometimes a piece that didn’t give the right feeling for one situation ends up working fine for another.

We’re still in the process of creating music, but it’s coming along nicely. I kept hearing “ChaosHorror” in my head even when I was working on other stuff, which I consider a good sign.

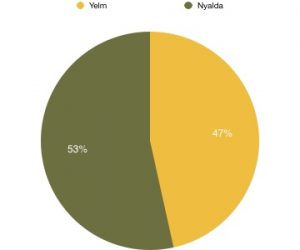

Players had no strong preference. 53% picked the Earth Goddess.

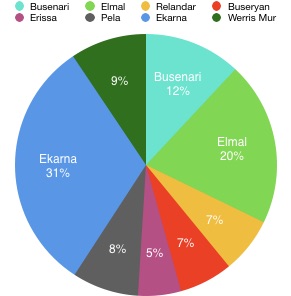

Players had no strong preference. 53% picked the Earth Goddess. The most popular gods to help were the trade goddess, the warlike sun, and the cow goddess.

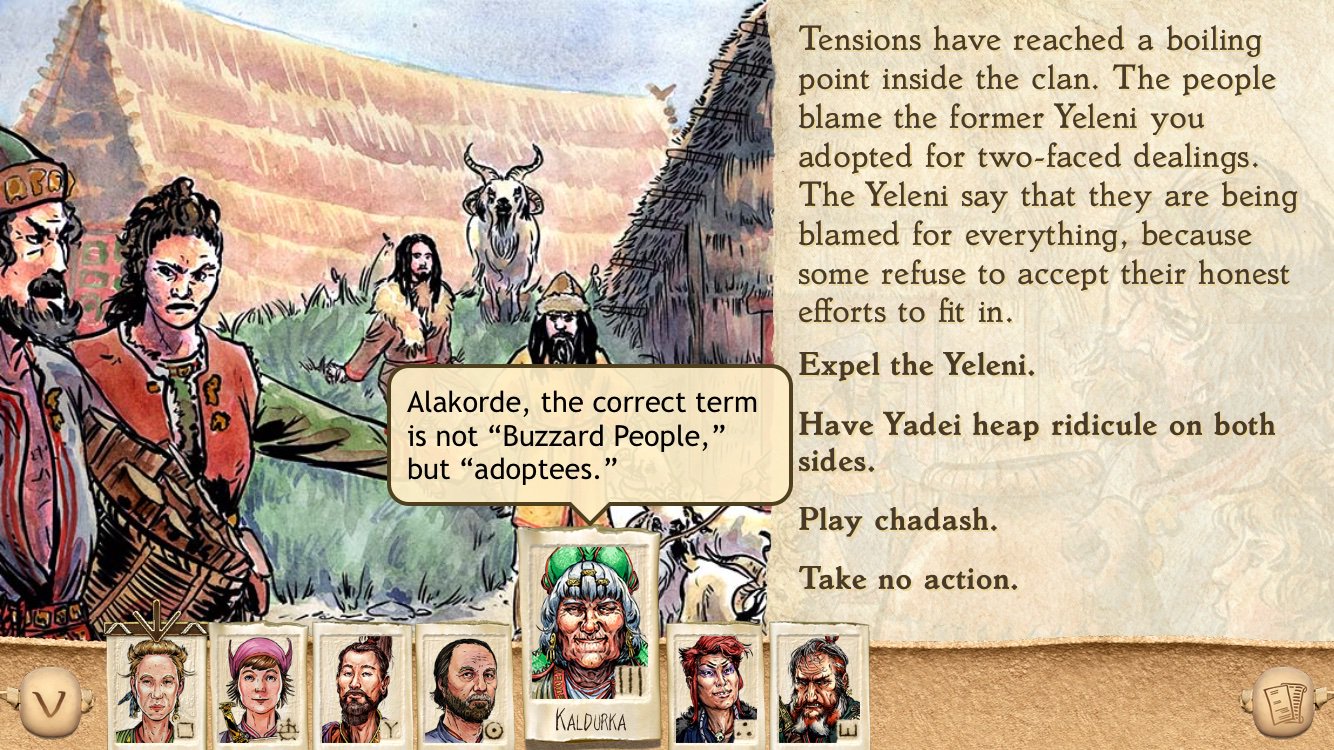

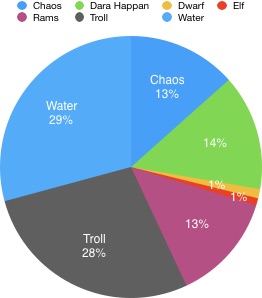

The most popular gods to help were the trade goddess, the warlike sun, and the cow goddess. The forces of water were a slight favorite. Perhaps players remembered that this was a weaker foe in King of Dragon Pass. (That’s not necessarily the case in this game.) Presumably the elves and dwarves are poorly represented here because both are not early enemies, and are available as choices only if you pick “Our worst danger came later.”

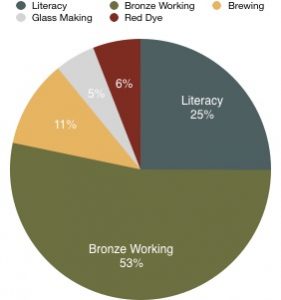

The forces of water were a slight favorite. Perhaps players remembered that this was a weaker foe in King of Dragon Pass. (That’s not necessarily the case in this game.) Presumably the elves and dwarves are poorly represented here because both are not early enemies, and are available as choices only if you pick “Our worst danger came later.” Apparently our players were keen to be master redsmiths, over half of them making sure to bring the god of bronze working as they fled their home. 25% retained literacy. Only 5% brought the secrets of glass making, which I guess is represented in the artwork (other than the user interface, I don’t think we explicitly show any glass).

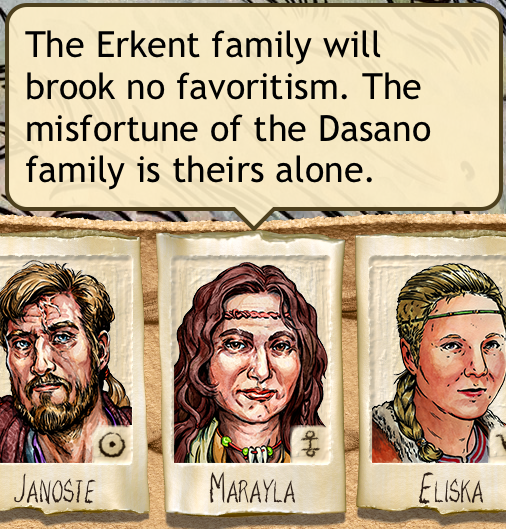

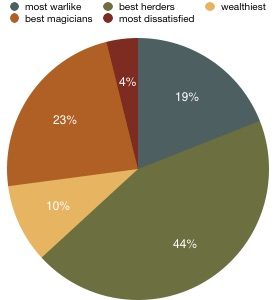

Apparently our players were keen to be master redsmiths, over half of them making sure to bring the god of bronze working as they fled their home. 25% retained literacy. Only 5% brought the secrets of glass making, which I guess is represented in the artwork (other than the user interface, I don’t think we explicitly show any glass). Given the importance of herding to the Riders, it’s not surprising that 44% of players decided that their ancestors were the best herders in the First Clan. I always figured that the most dissatisfied members were the ones who most wanted to split, but this isn’t a popular choice.

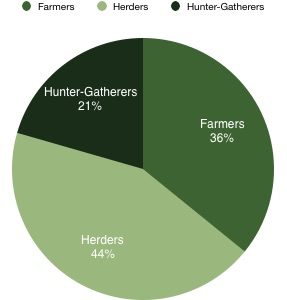

Given the importance of herding to the Riders, it’s not surprising that 44% of players decided that their ancestors were the best herders in the First Clan. I always figured that the most dissatisfied members were the ones who most wanted to split, but this isn’t a popular choice. The most popular choice was herders, followed by farmers.

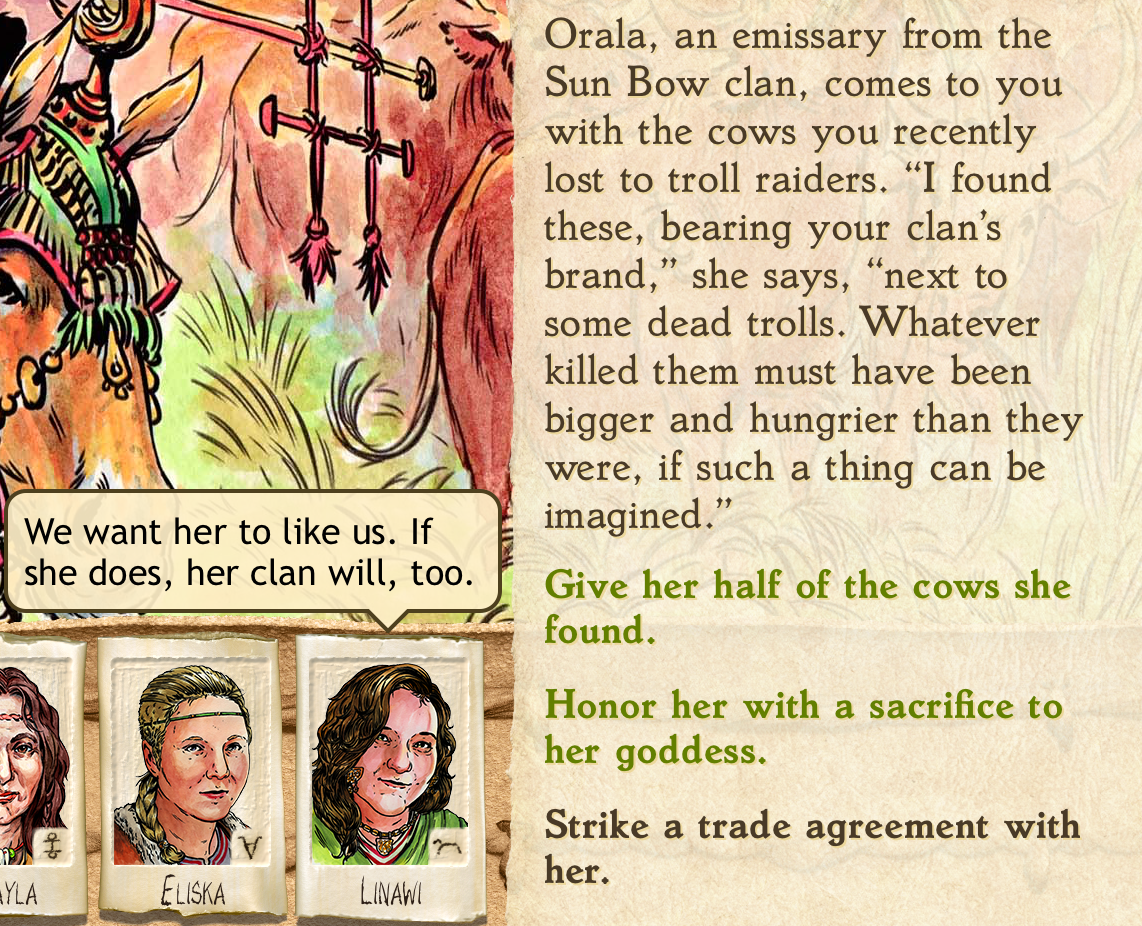

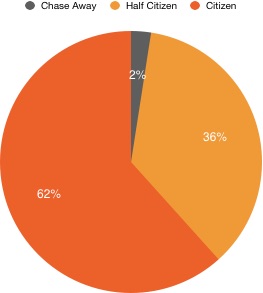

The most popular choice was herders, followed by farmers. Almost everyone adopted them, and most players made them full citizens of the clan.

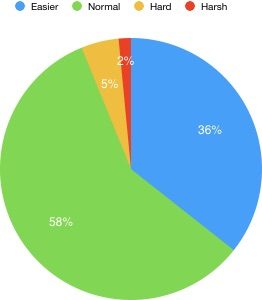

Almost everyone adopted them, and most players made them full citizens of the clan. The final question is primarily to establish your starting conditions. This is a difficult game, so it’s totally fine to start at the Easier setting. Most games were started at Normal. Probably players only play at Harsh once they have mastered things.

The final question is primarily to establish your starting conditions. This is a difficult game, so it’s totally fine to start at the Easier setting. Most games were started at Normal. Probably players only play at Harsh once they have mastered things. I’ve

I’ve  We came up with a

We came up with a

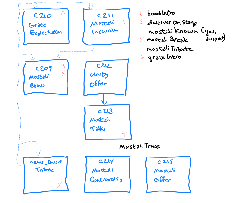

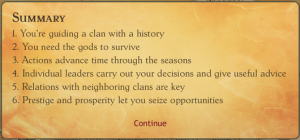

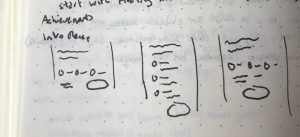

I want to show an explanation of the chosen difficulty, so I mocked up a couple UI designs. Now that it’s in the game, I may further tweak the intro (because it is indeed one more choice, and takes up space on a screen that may make other items less prominent).

I want to show an explanation of the chosen difficulty, so I mocked up a couple UI designs. Now that it’s in the game, I may further tweak the intro (because it is indeed one more choice, and takes up space on a screen that may make other items less prominent).