What’s your background?

I have a master’s degree in computer science. About half my career has been working on general software (like the Opal outliner and the built-in book reader for Apple Newton), and the rest on computer games (including paid gigs at Shenandoah Studio and GameHouse).

How did you get into the industry?

Illustration by Ellen Barkin

I first started working with computers for money while in high school, though this was more keypunching and other operations-type things for the library and the school district than actual programming. I did some of that while in college.

My first game writing was for the fanzine Alarums & Excursions, which was my initial connection with Robin Laws.

I got into the overall game industry by writing articles and reviews for game magazines like Different Worlds and Space Gamer. This connected me with people like Greg Stafford and Forrest Johnson.

I was also part of the community of Glorantha fans, both online and at conventions. That’s certainly how I ended up being able to do King of Dragon Pass with Robin Laws (he writes about our meeting at Glorantha Con 4).

What was the first gaming product you worked on, and in what capacity?

The first two digital games I made aren’t really products. I made an American football game while I was in middle school. My friend and I played it on the Olivetti Programma 101. You’d pick a play by running a secretly-chosen magnetic card though the reader, the defender would type something, and then the offense could type an “audible” to react. We had to keep track of field position and score separately, since each play was reprogramming the device from scratch via the card.

And I collaborated with Forrest Johnson on a text adventure game which was probably too ambitious, and was never finished. I was the programmer, and Forrest did the text. We had a nice working prototype, but were trying to come up with a system that could handle almost anything. Basically, it was an engine for parser-based text games.

How were you introduced to Glorantha?

Technically it was because a friend and I were looking to play something together, and I bought a copy of White Bear & Red Moon. I’m not sure we ever did play it. I did send in the included postcard, and Greg Stafford sent back a copy of his zine, which expanded the game a little and had some information about the setting. I don’t think any of it really stuck (though I saved the copy of Wyrms Footnotes).

My real introduction was through RuneQuest and Cults of Prax, which fleshed out Glorantha enough to be truly complelling. I played in Ron Boerger’s campaign which quickly ended up in Pavis and the Big Rubble, wandered up to Griffin Mountain, and spent time in the Borderlands. (My character in Ron’s game makes an appearance in King of Dragon Pass.)

What inspired the format of King of Dragon Pass?

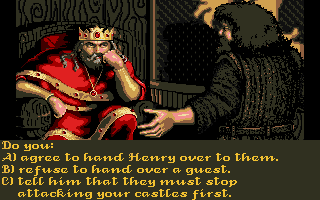

Greg Stafford and I worked up the basic game structure, first by mail and eventually in person. For me, the big inspiration was the 1991 computer game Castles, designed by Scott Bennie. The basic game was about building castles, and defending them against attackers. There were also random interruptions, where you had to make decisions about minor crises, such as your workers being terrified by a werewolf. I found this more interesting than making castles and wanted to make this a core part of the game, rather than something that didn’t seriously affect game play.

The Icelandic family sagas were a big factor too — plucky settlers farming and adventuring over multiple generations.

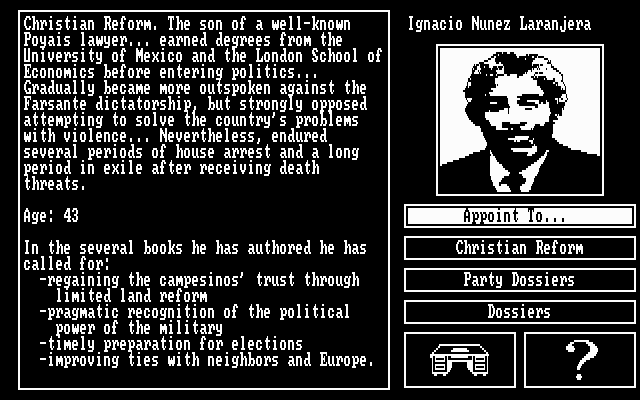

I can’t speak for all of Greg’s inspiration, but I do remember on my visit he made a point of showing me the 1988 game Hidden Agenda (I recollect it as all green, though perhaps that was his monitor as screen shots seem to be white on black). While you’re also dealing with crises, the key element here was picking your advisors.

It wasn’t much of a stretch to make this Gloranthan, picking your clan council instead of cabinet ministers.

How did it develop from your first conception to the final game?

The basic outline of King of Dragon Pass must have crystalized pretty quickly, because I think the final game is actually pretty close to that first conception. Obviously there were a lot of details that needed to be added, like the look of the Orlanthi, tribal negotiation, the scripting language, and heroic combat. But it always had advisors commenting on decisions that were linked via an economic model (which they also commented on depending on their expertise).

What was the most challenging part of the project?

In Six Ages, making sure the player knows what to do turned out to be a problem. One aspect of this was explaining the basics of game play. We’d come up with a nice system of contextual tips, but it wasn’t until we had people who had never played King of Dragon Pass try the game that we realized that the tips didn’t really give you an overview of how to play. Especially since several aspects of the experience are very different from other games. So we had to create a short scripted tutorial.

The other aspect is that it’s hard to communicate the goal of the game when it involves something of a plot twist. In King of Dragon Pass, the name of the game tells you your objective. I tried to add as much foreshadowing and explanation as possible, given the constraint that it has to be conveyed in-game by advisors who don’t have any idea about the plot twist either.

An alternate answer might be: bringing the game to more platforms. (In an area where we got lucky with King of Dragon Pass, we were unlucky, repeatedly.) Fortunately it looks like the current approach will succeed.

What was the best part of the project?

Making King of Dragon Pass was one of the great experiences of my life. I worked with some extremely talented people to create something that had never been made.

Six Ages couldn’t quite capture that (for example, Greg Stafford had retired, and this was a essentially sequel rather than a groundbreaking game), but it was another chance to create a pretty special game. And once again I was working with some amazing talent. This was an opportunity I had been hoping to have, and it finally worked out.

And it was a chance to make a similar game after having worked another ten years or so in the computer game business, and put into practice everything I’d learned since making King of Dragon Pass.

Other than Six Ages or King of Dragon Pass, what’s your favorite computer game?

That’s always a hard question! I’ve been playing them since the 1970s, which covers a lot of games. On the other hand, I’ve spent a lot of that time making games, which meant I don’t play them quite the same way most players might.

These days I seem to spend most of my relaxation gaming on games that I can play away from my desk, and which I can dip in and out of. Two Dots on iPad is a tactile experience — but I doubt I would enjoy it on a computer screen despite very competent design. And I have been playing Fallen London in a web browser for years, for its great writing. I don’t know if it’s a factor but both of these have mechanisms that cap my play time, which might prevent burnout.

I suspect my favorite is The Secret of Monkey Island, which was funny and well crafted, with a great soundtrack. And the satisfying ending was one of the inspirations for King of Dragon Pass.